Mauna Kea

| Mauna Kea | |

|---|---|

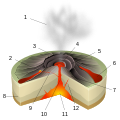

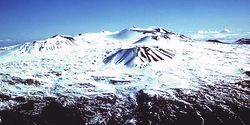

Mauna Kea with its seasonal snowcap visible |

|

| Elevation | 4,205 m (13,796 ft) NAVD 88 [1] |

| Prominence | 4,205 m (13,796 ft) Ranked 15th |

| Listing | Ultra US state high point |

| Pronunciation | [English pronunciation: /ˌmɔːnə ˈkeɪ.ə/ or /ˌmaʊnə ˈkeɪ.ə/, Hawaiian pronunciation: [ˈmounə ˈkɛjə]] |

| Location | |

Mauna Kea

|

|

| Location | Hawaii County, Hawaii, United States |

| Range | Hawaiian Islands |

| Coordinates | [2] |

| Geology | |

| Type | Shield volcano, hotspot volcano |

| Age of rock | Oldest dated rock: 237,000 ± 31,000 BP[2] Approximate: ~1 million[2] |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Hawaiian – Emperor seamount chain |

| Last eruption | 6,000 to 4,000 years ago[2] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | Recorded: Goodrich (1823)[3] |

| Easiest route | Mauna Kea Trail |

Mauna Kea is a dormant volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi. Standing 4,205 m (13,796 ft) above sea level, its peak is the highest point in the state of Hawaiʻi. However, a significant part of the mountain is under water; when measured from its oceanic base, Mauna Kea is over 10,000 m (33,000 ft) high, significantly higher than Mount Everest. This great height is due mostly to its advanced age. Being about a million years old, Mauna Kea's most active shield stage of life was hundreds of thousands of years ago. In its current post-shield state, its erupted lavas are more viscous and have created a steeper profile. Late volcanism has given it a much rougher appearance than its neighboring volcanoes; contributing factors are the construction of cinder cones, the decentralization of its rift zones, glaciation on its peak, and the weathering effects of the prevailing trade winds.

In Hawaiian mythology, the peaks of the island of Hawaiʻi are sacred, and Mauna Kea is the most sacred of all. A kapu (ancient Hawaiian law) allowed only high-ranking tribal chiefs to visit its peak. Ancient Hawaiians living on the slopes of Mauna Kea relied on its extensive forests for food, and quarried the dense volcano-glacial basalts on its flanks for tool production. When Europeans arrived in the late 18th century, settlers introduced cattle and sheep, many of which became feral, invasive species and game animals, damaging the mountain's ecology. Mauna Kea can be ecologically divided into three sections: an alpine climate at its summit, a māmane–naio forest on its flanks, and an Acacia koa–ʻōhiʻa forest, now mostly cleared by the local sugar industry, at its base. In recent years, concern over the vulnerability of the native species has led to court cases that have forced the state to eradicate all feral species on the mountain.

Mauna Kea's summit is one of the best sites in the world for astronomy, because of its high altitude, dry environment, and stable airflow. Since the creation of an access road in 1964, thirteen telescopes funded by eleven countries have been constructed at the summit, conducting many research project as the largest facility of its class in the world. The Mauna Kea Observatory has since become a point of debate, both ecologically and culturally. Studies are trying to determine its effect on the summit ecology, particularly on the rare wēkiu bug. Culturally, the construction represents development on a summit that had once been sacred.

Contents |

Geology

Mauna Kea stands 4,205 m (13,796 ft) tall,[2] just 35 m (115 ft) higher than its neighbor Mauna Loa.[2] Mauna Kea is the highest peak on Earth in terms of dry prominence; that is, since Mauna Kea forms the structure of the island, when measured from oceanic base to subaerial peak (versus height defined above sea level, "wet prominence"), it stands over 10,000 m (32,808 ft), higher than Mount Everest.[4] This vertical drop was caused by late eruptions of highly viscous lavas that have built a steep edifice.[5]

Mauna Kea is a hotspot volcano and part of the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, a long volcanic chain that was spawned by the Hawaii hotspot. It forms part of the island of Hawaiʻi, the largest and youngest island of the chain.[6] Of the five volcanoes that make up the island, Mauna Kea is both the fourth oldest and fourth most active.[2] Like the other older Hawaiian volcanoes, Hualālai and Kohala, Mauna Kea has evolved beyond the active shield-building stage of its life, having entered its post-shield stage 200,000 to 250,000 years ago. The volcano is currently dormant, as indicated by its steeper shape, lower eruption rates, and lava types differing from those of its active neighbors. These changes in the volcano's life cycle indicate that the supply of magma to the summit is slowly being cut, weakening eruptions until they give way to isolated instances of brief eruptions that solidify quickly. The lava from Mauna Kea is more viscous and contains more volatiles than that of younger volcanoes, resulting in thicker flows that steepen the volcano's flanks, and explosive eruptions that build cinder cones, of which Mauna Kea has several, on the volcano's summit.[2] These are constructed of alkalic basalt as opposed to the tholeiitic basalt of younger Hawaiian volcanics.[7] However, the volcano is expected to erupt again in the future.[2]

The Laupāhoehoe and Hāmākua volcanic clasts are the two predominant lava series on the volcano. The Hāmākua volcanics are the oldest exposed rock strata on Mauna Kea, and are prevalent on much of the volcano's slope. Geologists usually divide it into two sections by age, one associated with shield stage volcanism and one with post-shield volcanism. As the transition line between basaltic shield lavas and alkaline post-shield lavas is difficult to determine, it may only be shield stage lava, dated widely between 300 and 64 ka. In contrast the Laupāhoehoe volcanics are the youngest volcanic flows, consisting of hawaiite, mugearite, and benmoreite. Charcoal dating puts the flow at 8,200 to 4,580 years of age. In addition many rock cores have been collected from Mauna Kea, indicating an age range of 1,000 to 3,000 years at 1 m (3.3 ft) of depth, going up to 6,000 to 9,000 years at 3 m (9.8 ft).[7]

Mauna Kea's summit is not as well defined as other Hawaiian volcanoes. Volcanic lineaments and ridges produce a "bumpy" shape. The construction of cinder cones late in the volcano's life helped decentralize its structure.[8] Mauna Kea's summit was covered by a massive ice cap during past ice ages. Glacial moraines formed on the volcano approximately 70,000 and 40,000 to 13,000 years ago, leaving behind till and outwash. Mauna Kea is the only Hawaiian volcano with distinct evidence of glaciation;[8] similar deposits probably existed on the similarly high Mauna Loa but have since been covered by lava flows.[2] The three principal glacial forms are the Pōhakuloa (180–130 ka), Wāihu (80–60 ka), and Mākanaka (40–13 ka) ice caps. A small body of permafrost, just 25 m (82 ft) across, survives on the summit of Mauna Kea.[7]

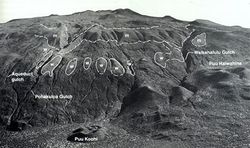

The summit of Mauna Kea is dominated by scoria cones and lava domes. The largest stand at 1.5 km (0.9 mi) in diameter and a few hundred meters tall. These cones were the late eruptive centers of Mauna Kea and are surrounded by the lava flows from approximatly 65,000 to 14,000 years ago. These cones were active during the most recent period of glaciation (the Mākanaka ice cap[7]) 43,000 to 13,000 years ago, resulting in subglacial eruptions.[9]

On the windward side, stream erosion driven by trade winds accelerated erosion in a manner similar to Kohala, the oldest volcano on the island.[10] The summit of Mauna Kea is more youthful than its slopes, being made of newer lavas and having thus stood against less erosion; and it is littered with cinders, volcanic bombs, and coarsely soiled rock.[3] Small gullies also etch the summit, formed by rain- and snow-fed streams existing only during winter melt and rain showers.[11] The volcano is currently slipping under its own weight at a rate of less than 0.2 mm (0.01 in) per year.[2]

East of Mauna Kea, the prominent underwater rift zone structure of Hilo Ridge stands 3,000 m (9,843 ft) tall and 50 km (31 mi) long. Hilo Ridge was once believed to be a part of Mauna Kea; however, it is really a rift zone of the nearby Kohala that has been affected by younger flows from Mauna Kea.[7][12] The original rift zones of Mauna Kea, once inactive, were buried by post-shield volcanism. Lava may or may have not followed old rift pathways during late-stage volcanism.[8]

Mauna Kea is home to Lake Waiau. At an altitude of 3,969 m (13,022 ft), it is the only alpine lake in Hawaii state[13] and the 7th highest lake in the United States. However the lake is very small, (0.73 ha (1.80 acres) across), and shallow, at just 10 ft (3 m) deep. Radiocarbon dating of samples at the base of the lake indicate that it was clear of ice 12,600 years ago. The lake is one of the few permanent lakes in Hawaiʻi; while Hawaiian lavas are typically permeable, at Lake Waiau, either steam eruptions or lava-water eruptions from its parent cone Puʻu Waiau lined the lakebed with a seal of fine particles. This hastened the erosion of the cone and allowed the lake to retain water.[13]

Future activity

Mauna Kea has seen no historic eruptions; the volcano's last eruption was about 4,600 years ago.[7] Because of its inactivity, Mauna Kea is assigned a USGS hazard listing of 7 for its summit and 8 for its lower flanks, out of the lowest possible hazard rating of 9 (for extinct volcano Kohala). Twenty percent of the volcano's summit has seen lava flows in the last 10,000 years, and its flanks have seen virtually no lava flows within that time.[14]

Despite being dormant, Mauna Kea is expected to erupt again, although with sufficient warning. The first to detect activity would be telescopes on Mauna Kea's summit, as they can detect the sensitive coordinate changes that would result from the volcano's swelling, acting like an expensive tiltmeter. Based on recent eruptions, such an event could occur anywhere on the volcano's upper flanks and would likely produce extended lava flows, mostly of a'a, extending 15–25 km (9–16 mi). Extended activity would build a cinder cone at the source. Although not likely in the next few centuries, such an eruption would probably result in little loss of life but great damage to infastructure.[5]

Human history

Native history

Ancient Hawaiians first arrived on Hawaiʻi island and lived along the shores, where food and water were plentiful. Over time, settlers acclimated to their new environment and, with stable food resources, expanded inland, finally living in the Mauna Loa–Mauna Kea region in the 12th and early 13th centuries.[15] The mountain's plentiful forest provided plants and animals for food and raw materials for shelter. Flightless birds that had previously known no predators became a staple food source.[16]

The summits of the five volcanoes of Hawaiʻi are revered as sacred; and Mauna Kea's summit, being the tallest, was the most sacred of all. For this reason, a kapu reserved visitor rights for high-ranking tribal chiefs only. Hawaiians regarded all parts of their natural environment as being associated with a certain deity. In Hawaiian mythology, the sky father Wākea marries the earth mother Pāpā, giving birth to the Hawaiian Islands. In many of these genealogical myths, Mauna Kea is portrayed as the pair's first-born son. The Hawaiians themselves were also connected to this web. The summit of Mauna Kea was seen as the "region of the gods," a place where spirits, both good and benevolent, reside.[16] Poliʻahu, deity of snow, also resides there.[17] In Hawaiian, Mauna Kea means "white mountain,"[18] a reference to its summit, which is usually snow-capped in winter.[19] The mountain is also known as Mauna o Wākea, or "Mountain of (the deity) Wākea."[20]

In approximatly AD 1100 natives established quarries high on Mauna Kea. Uniquely dense basalt, highly valuable in the manufacture of tools, was generated there by subglacial eruptions in the volcano's past. Volcanic glass and gabbro were also collected for cutting tools and fishing gear, and māmane wood was preferred for the handles. At its peak use in the 15th century, there were separate facilities for rough and fine cutting; shelters containing food, water, and wood to sustain quarry workers during extended work periods; and workshops producing the finished product.[16]

Lake Waiau, one of the highest lakes in the world and the highest alpine lake in the Pacific Basin,[21] provided drinking water for the workers. Native chiefs would dip the umbilical cords of newborn babies in the water, to give them the strength of the mountain.[22] Use of the quarry started to decline between this period and contact with Americans and Europeans. As part of the ritual associated with quarrying, the workers erected shrines to their gods; and these and other quarry artifacts remain at the sites, most of which lie within what is now the Mauna Kea Ice Age Reserve.[16]

The early era was followed by peace and cultural expansion between the 12th and late 18th century. Land was divided into regions designed for both the immediate needs of the populace and the sustenance of the long-term welfare of the environment. These ahupuaʻa were long strips of land reaching from a mountain's summit to the coast. Mauna Kea's summit was encompassed in the ahupuaʻa of Kaʻole, with part of its eastern slope reaching into the nearby Humuʻula. Principal sources of nutrition for Hawaiians living on the slopes of the volcano came from the māmane–naio forest of its uppers slopes, which provided them with both vegetation and bird life for nutrition. Hunted bird species included the ʻuaʻu (Pterodroma sandwichensis), nēnē (Branta sandvicensis), and palila (Loxioides bailleui). The lower acacia koa–ʻōhai forest, meanwhile, gave the natives wood for canoes and ornate bird feathers for decoration.[16]

Modern era

The first foreigner to arrive at Hawaiʻi was James Cook (1778).[11] The earliest Western depictions of the isle, including Mauna Kea, were compiled by explorers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Contact with Europe and America had major consequences for the island residents. Native Hawaiians were devastated by introduced disease; port cities like Hilo, Kealakekua, and Kailua grew with trade with the Americans; and the adze quarries on Mauna Kea were abandoned with the introduction of metal tools over stone ones.[16]

In 1793, cattle were brought by George Vancouver as a tribute to King Kamehameha I. By the early 1800s, many stocks had escaped confinement and roamed the island freely, becoming a great source of damage to the ecosystem. In 1809 John Palmer Parker arrived at the island and befriended Kamehameha I, who put the man in charge of cattle on the island. With an additional land grant in 1845, Parker established Parker Ranch on the norther slope of Manua Kea, a large cattle ranch that is still in operation today.[16] Settlers to the island burned and cut down much of the native ecosystem for the construction of sugar plantations and residences.[23]

1943 marked the construction of the Saddle Road, so named for its crossing of the saddle-shaped plateau between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. The Pohakuloa Training Area on the plateau is the largest military training ground in Hawaiʻi. The 108,863-acre (44,055 ha) base extends from the volcano's lower flanks to 2,070 m (6,791 ft) elevation, on state land leased to the US Army since 1956. There are 15 threatened and endangered plants, 3 endangered birds, and 1 endangered bat species in the area.[11]

Mauna Kea has been the site of extensive archeological research since the 1980s. Approximately 27 percent of the Science Reserve was surveyed by the year 2000, including 76 shrines, 4 adze manufacturing workshops, 3 other markers, 1 positively identified burial site, and 4 possible burial sites.[16] By 2009, the number of sites had climbed to 223, and archeological research on the volcano's upper flanks is still ongoing.[11] It has been suggested that the shrines, which are arranged around the volcano's summit along what may be an ancient snow line, are markers for the transition to the sacred part of Mauna Kea, its upper summit. The largest and most prominent quarries uncovered are those found in the Ice Age Reserve and are not included in this number.[16] Despite many references to burial around Mauna Kea in Hawaiian oral history, few sites have been confirmed. The lack of shrines or other artifacts on the many cinder cones dotting the volcano may be because they were reserved for burial.[16]

Ascent

In pre-contact times, natives traveling up Mauna Kea were probably guided more by landscape than by existing trails, as no evidence of the latter have been found. It is possible that natural ridges and water sources were followed instead. Individuals likely took trips up Mauna Kea's slopes to visit family-maintained shrines near its summit, and traditions related to ascending the mountain exist to this day. However, very few natives actually reached the summit, because of the strict regulation (kapu) placed on it.[16]

In the early 19th century, the earliest recorded ascents of Mauna Kea included:

- On August 26, 1823, Joseph F. Goodrich, an American missionary, made the first recorded ascent, in a single day; but he saw a small arrangement of stones, suggesting he was not the first human on the summit.[16] He noted three to four regions in passing from its base to its summit and visited Lake Waiau.[3]

- On June 17, 1825, an expedition from the HMS Blonde, led by botanist James Macrae, summited Mauna Kea. He was the first person to record the Mauna Kea silversword (Argyroxiphium sandwicense), saying:[3]

"The last mile of was destitute of except one plant of the Sygenisia tribe, in a growth much like a Yucca, with sharp pointed silver coloured leaves and green upright spike of producing pendulous branches with brown flowers, truly superb, and almost worth the journey of coming here to see it on purpose."—James Macrae[3]

- In January 1834, David Douglas climbed the mountain and described extensively the division of plant species by altitude. On a second climb in July, he was found dead in a pit intended to catch wild cattle. Although murder was suspected, it was probably an accidental fall. The site called Ka lua kauka , is marked by the Douglas Fir trees named for him.[24]

- In 1881, Queen Emma traveled to the peak to bathe in the waters of Lake Waiau, thus imbuing herself with the spirit of the land during her run for queen of the Kingdom of Hawaii.[16]

- On August 6, 1889, E.D. Baldwin left Hilo and followed cattle trails to its summit.[3]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, trails were formed, often traveled on horseback and game trails formed by the movement of herds.[16] However, vehicular access to the summit was essentially impossibe until the construction of a road in 1964, and it continues to be restricted.[25] Today, multiple trails exist to the summit, in various states of use.[11]

Ecology

Background

Hawaiʻi's geographical isolation is a dominating feature of its ecology. This remoteness results in an evolutionary line distinct from that anywhere else, and protects endemic species from external biotic influence. Remote islands like Hawaiʻi serve to promote species that can only be found, in small numbers, there and nowhere else. This makes them especially vulnerable to extinction and the effects of invasive species. In addition the ecosystem of Hawaiʻi is under threat from human development and the clearing of land for agriculture; an estimated third of the island's endemic species have already been wiped out.[23] Because of its height, Mauna Kea has the greatest diversity of biotic ecosystems anywhere in the Hawaiian archipelago. Ecosystems on the mountain form concentric rings along its slopes due to changes in temperature and precipitation with altitude.[23] These ecosystems can be roughly divided into three sections by height: alpine–subalpine, montane, and basal forest.[3]

Contact with Americans and Europeans in the early 19th century brought more settlers to the island, and had a lasting negative effect on the island ecologically. On lower slopes, vast tracts of acacia koa–ōhiʻa forest were reduced to farmland for the construction of homes and advancement of agriculture. Higher up, feral animals that escaped from ranches built on the island found refuge in, and damaged extensively, Mauna Kea's native māmane–naio forest.[26] Non-native plants are the other serious threat; there are over 4,600 introduced species on the island, wheras the number of native species is estimated at just 1,000.[27]

Alpine environment

The summit of Mauna Kea is entirely above the timberline, consisting of mostly lava rock and alpine tundra. The summit zone of Mauna Kea is an area of heavy snowfall, and is inhospitable to vegetation, an area known as the Hawaiian tropical high shrublands. Growth is limited at the summit by extremely cold temperatures, a short growing season, low precipitation, and the formation of snow banks during winter months. However, the largest limiting factor of the biome is its lack of soil, the formation of which has barely begun. This lack of material retards root growth, makes it difficult to absorb nutrients from the soil, and gives the area a very low water retention limit.[3]

Botanic species found at this height include Styphelia tameiameiae, Taraxacum officinale, Tetramolopium humile, Agrostis sandwicensis, Anthoxanthum odoratum, Trisetum glomeratum, Poa annua, Sonchus oleraceus, and Coprosma ernodiodes. Many of the species at this height are introduced, as the typically tropical climate of Hawaiʻi does not suite the hardy cold-weather plants that could live there. The most notable species at this hieght is Mauna Kea silversword (Argyroxiphium sandwicense var. sandwicense), a highly endangered endemic plant species that thrives at great heights. It was once thought to be restricted to alpine zone it is in fact driven there by pressure from livestock, and can grow at lower heights as well.[3]

The Mauna Kea Ice Age Reserve on the southern summit flank of Mauna Kea was established in 1981. The reserve is a region of sparsely vegetated cinder deposits and lava rock. Environments inside the reserve include aeolian desert and the alpine lake Lake Waiau.[28] The park's ecosystem is a likely haven for the threatened Hawaiian petrel (Pterodroma sandwichensis) and also the center of a study on wēkiu bugs (Nysius wekiuicola).[10]

Wēkiu bugs are remarkable in that they live off of dead insect carcasses that blow up Mauna Kea and collect on snow banks. This is a highly unusual food source for a species belonging to a family of predominantly seed-eating insects. They can survive at extreme heights of up to 4,200 m (13,780 ft)[29] because of antifreeze in their blood. The wēkiu bug is a cause for concern among conservation specialists, as it is not well understood what the effect the summit observatories on Mauna Kea have on the species. Studies on the welfare of the species began in 1980. The closely related Nysius aa was discovered on the nearby Mauna Loa in 1985, although it was not recognized as a separate species until 1998. The Mauna Loa bug is in less danger as it is not threatened by summit facilities.[30]

Although Wēkiu bugs are not the most unusual specimens found near the summit of Mauna Kea, they are the only ones. wolf spiders (Lycosidae) and moth caterpillars have also been observed on the volcano. Wolf spiders survive by hiding under heat-absorbing rocks, and moth caterpillars have antifreeze in their blood. Wēkiu bug are in between the two; although they also contain antifreeze to facilitate survival, they prefer staying under heated surfaces most of the time.[30]

Māmane-Naio forest

The highest forested zone on the volcano, at an elevation of 2,000–3,000 m (6,562–9,843 ft), is dominated by Māmane (Sophora chrysophylla) and Naio (Myoporum sandwicense), both endemic species with ties to similar species in New Zealand and the South Pacific. This area is thus known as the māmane–naoi forest. Māmane seeds and Naoi fruit are the chief food of the birds in this zone, especially the Palila (Loxioides bailleui). The Palila used to range on the slopes of Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Hualālai, but is now confined to the slopes of Mauna Kea; this represents 10% of its former range, and the species has been declared critically endangered.[23]

The largest threat to this ecosystem is grazing by feral sheep (Ovis aries), cattle (Bos primigenius),[31] mouflon (Ovis aries orientalis), and goats (Capra hircus) introduced onto the island in the late 18th century. Damage to the ecosystem was severe enough to establish a program to eradicate them as far back as the late 1920s,[23] which continued through to 1949. One of the results of this grazing was the increased prevalence of herbaceous and woody plants, both endemic and introduced, that were resistant to browsing.[31] The feral animals were almost eradicated, and numbered a few hundred in the 1950s, however an influx of local hunters at the time drove an increased value of the feral species as game animals, and in 1959 the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, the governing body in charge of conservation and land use management, changed its policy to a sustained-control program designed to facilitate the sport.[23]

1962 saw the further introduction of mouflon, and in 1964 Axis deer (Axis axis) were almost introduced, but were retracted due to protests from the ranching industry, who said that they would damage crops and spread disease. The hunting industry fought back, and the back-and-forth between the ranching industry and hunters eventually gave way to a rise in public environmental concern.With the development of astronomical facilities on Mauna Kea ongoing, conservationists demanded a plan to protect Mauna Kea's ecosystem. The plan was to fence of 25% of the forests from foreign influence, and leave the remaining 75% under the same regulations. Despite extreme opposition from conservationists the plan was put into action. While the land was partitioned no money was ransomed for the building of the fence. In the midst of this wrangling the Endangered Species Act was passed; the National Audubon Society and Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund filed suite against the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, claiming that they were violating federal laws of conservation in the landmark case Palila v. Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources (1978).[23][32]

The court ruled in favor of conservationists and upheld the precedence of federal laws before state control of wildlife. Having violated the Endangered Species Act, Hawaii state was required to remove all feral animals from the mountainside.[23] This was followed by a second court order in 1981. A public hunting program eradicated the feral animals, although there are some concerns of resurgence.[26] An active control program is in place to keep their numbers in check.[11] Although the Māmane-Naoi ecosystem received a reprieve, there are many other species and ecosystems on the island, and on Mauna Kea, that remain threatened by human development and invasive species.[23]

The Mauna Kea Forest Reserve protects 52,500 acres (21,246 ha) of māmane-naio forest under the jurisdiction of the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources. Ungulate hunting is allowed year-round.[11] A small part of the Māmane-Naoi forest is encompassed by the Mauna Kea State Recreation Area.[33]

Lower environment

At the lower slopes of Mauna Kea there is a band of ranch land which was formerly Acacia koa-'ōhi'a forest.[3] The destruction of the forest was driven by an influx of European and American settlers following contact with Hawaiʻi in the early 19th century. During the 1830s the forest was the site of an extensive logging campaign to provide lumber for new homes. In addition vast swatches of the forest were burned and cleared for the construction of sugar plantations on the island. Most of the houses on the island were built entirely of koa, and the parts of the forest that survived the campaign were continuously revisited for firewood to power boilers on the sugar plantations and to heat homes. The once vast forest had almost disappeared by 1880, and by 1900 logging interests had shifted to Kona and Maui, the upper vestiges of the forest having been almost entirely converted entirely to ranch land.[26] With the collapse of the sugar industry in the 1990s, much of this land lies fallow but portions are used for cattle grazing, small-scale farming and the cultivation of eucalyptus for wood pulp.[34]

The Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge is a major wildlife refuge protecting koa forest on Mauna Kea's windward slope. It was established in 1985 on one of the last remaining tracts of forest. The refuge measures 32,733 acres (13,247 ha) in size and protects many endangered native species. Eight endangered bird species and twelve endangered plants have been observed in the area, in addition to many other rare biota. The endangered Hawaiian hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus semotus) is also known to frequent the region. The reserve has been the site of an extensive replanting campaign since 1989.[35] Parts of the reserve can be seen as an example of the effect agriculture has on the native ecosystem,[26] as much of the land in the upper part of the reserve consists of abandoned farmland, now fallow.[35]

Bird species native to the acacia koa–ʻōhiʻa forest include the Hawaiian crow (Corvus hawaiiensis), the ʻAkepa (Loxops coccineus), Hawaiʻi Creeper (Oreomystis mana), ʻAkiapōlāʻau (Hemignathus munroi), and Hawaiian Hawk, (Buteo solitarius), all of which are endangered, threatened, or near threatened; the Hawaiian crow in particular is extinct in the wild, with plans to reintroduce the species into the Hakalau reserve.[35]

Summit observatory

Mauna Kea's summit is one of the best in the world in terms of astronomical observation.[36][37][11] The atmosphere above the volcano is extremely dry, an important factor in submillimeter and infrared astronomy. This is because the summit is above the inversion layer that separates lower maritime air from upper atmospheric air, ensuring the air on the summit is pure, dry, and free of atmospheric pollution. The summit is above most cloud cover, the atmosphere is stable, and light pollution from the surrounding areas is low.[36] This made Mauna Kea an excellent spot for stargazing long before the summit telescopes were proposed.[25]

The construction of a summit observatory on the volcano was suggested as early as 1909. Tests conducted by the University of Hawaii in 1964 substantiated earlier claims as to the pristineness of the summit and its suitability for potential astronomical observatories. After more tests were conducted in 1965 and 1966, the university contacted NASA to design and build its University of Hawaiʻi 88 in (2.2 m) telescope. The next year the Institute for Astronomy, the University of Hawaii branch responsible for managing the summit observatories, was created.[11] In 1968, the institute was given a 65-year land lease by the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources for all land within a 4 km (2.5 mi) radius of the original telescope, an area of approximately 13,321 acres (5,391 ha) and essentially all the land on the volcano above 3,700 m (12,139 ft). With the land secured and the design submitted, construction on the observatory began.[36][11]

By 1974, three telescopes had been constructed on Mauna Kea. At that point, opposition began to arise on the part of indigenous Hawaiians, for whom the construction constituted a desecration of a sacred site. Local groups also started to raise concerns on the environmental impact of the site. The response came in the form an initial management plan, drafted in 1977 and supplemented in 1980.[11] In January 1982, the University of Hawaii's Board of Regents approved a plan for the management of the reserve. The basic goal outlined by the plan was to foster the development of the observatory as a preeminent site for astronomical observations. The 1982 plan was replaced in 2000 by an extension designed to serve astronomical, ecological, and cultural needs up to the year 2020.[37] The 2000 plan designated 525 acres (212 ha) for astronomy, and the remaining 10,763 acres (4,356 ha) were designated for natural and cultural preservation. The plan was further adjusted in 2009.[11]

Today the Mauna Kea Science Reserve is the site of 13 observatories from 11 countries, the largest such array in the world. 2,033 acres (823 ha) were withdrawn in 1998 to supplement the Mauna Kea Ice Age Reserve. The Office of Mauna Kea Management is responsible for the day to day management of the observatory,[11] which has telescopes with mirrors ranging from 0.6 m (2.0 ft) to 25 m (82 ft) and constructed between the years 1968 and 2002. In comparison, the Hubble Space Telescope has a 2.4 m (7.9 ft) mirror, comparable in size to the second smallest telescope on the mountain, and thus the observatory has 60 times the light-gathering power, allowing astronomers to see farther (although not quite as clearly).[38][36][39][40] There are 9 telescopes working in the visible/infrared spectrum, 3 in the submillimeter spectrum, and 1 in the radio spectrum.[39] In addition, two new telescopes, Pan-STARRS and the Thirty Meter Telescope, are planned projects for the summit.[41][42] The observatory continues to be a site of controversy (see Ecology).[43]

Recreational significance

Mauna Kea's coastline is dominated by the Hamakua Coast, an area of rugged terrain generated by the effect of trade winds on the volcano's flank. Watershed-generated rivers form the center of many popular recreation areas including Kalopa State Recreation Area, Wailuku River State Park and Akaka Falls State Park.[44]

There are over 3,000 registered hunters on Hawaiʻi island, and hunting, for both recreation and sustenance, is a common activity on Mauna Kea. A public hunting program is used to keep the numbers of some animals low, as introduced animals including pigs, sheep, goats, turkey, pheasants, and quail are highly damaging to the local ecosystem.[23][11] The Mauna Kea State Recreation Area functions as a base camp for the sport.[25] Birdwatching is also common at lower levels on the mountain.[36]

Mauna Kea's great height and the steepness of its flanks attract mountaineers, providing a better view and a shorter hike than the adjacent Mauna Loa.[22] However, these factors also make the volcano dangerous, as high elevation, weather concerns, steep road grade, and overall remoteness make summit trips difficult. Prior to the construction of road facilities in the mid 20th century, only hardy recreationists visited Mauna Kea's upper slopes; hunters tracked game animals, and hikers traveled up the mountain. These travellers used stone cabins on the volcano's flank, constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, as a base camp, and it is from these facilities that the modern mid-level Hale Pōhaku telescope support complex is derived. The first Mauna Kea summit road was built in 1964, and opened the exploration of the mountain to a wider audience.[25]

Today, multiple hiking trails including the Mauna Kea Trail exist, some more distinct then others, and an estimated 100,000 tourists and 32,000 vehicles go to the visitor's center at the Onizuka Center for International Astronomy every year. The Saddle Road is paved up to the Center at 2,804 m (9,199 ft).[11] Visitors travelling up the volcano's flanks are recommended to stop for at least half an hour and preferably longer at the visitor's center to acclimate to the higher elevation.[45] Driving all the way to the top requires four wheel drive vehicles, and brakes can often overheat on the way down.[45] 5,000 to 6,000 people summit Mauna Kea every year, and to help ensure safety, a ranger program was implemented in 2001.[11]

Because of the snow cover on Mauna Kea in January and February, Mauna Kea can occasionally be skied. There are no facilities,[11] and winds can reach speeds of 80–110 km/h (50–68 mph),[19] however it remains a popular pastime for some island residents. The most popular location is the Poi Bowl, just east of the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory,[11] where competitions are held once or twice a year, depending on weather conditions.[25]

See also

- Peak lists

- Mountain peaks of the United States

- Table of the ultra-prominent summits of the United States (2nd)

- Table of the most isolated major summits of the United States (2nd)

- Table of the highest major summits of the United States (59th)

- List of islands by highest point (2nd)

- List of peaks by prominence (15th)

- List of Ultras in Oceania (2nd)

- List of U.S. states by elevation (6th)

- Hawaii volcanics

- Evolution of Hawaiian volcanoes

- Hawaii hotspot

References

- ↑ "Summit USGS 1977". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. http://www.ngs.noaa.gov/cgi-bin/ds_mark.prl?PidBox=TU2314. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 "Mauna Kea: Hawai`i's Tallest Volcano". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory - USGS. 22 May 2002. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanoes/maunakea/. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Hartt, Constance E; Constance E. Hartt and Marie C. Neal (April 1940). "The Plant Ecology of Mauna Kea, Hawaii". Ecology (Ecological Society of America) 21 (2): 237–266. doi:10.2307/1930491. http://www.jstor.org/pss/1930491. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ Staff authors. "Highest Mountain in the World". Geology.com. http://geology.com/records/highest-mountain-in-the-world.shtml. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The next eruption of Mauna Kea". Hawaii Volcano Observatory - USGS. 5 June 2000. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/2000/00_06_01.html. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ Watson, Jim (5 May 1999). "The long trail of the Hawaiian hotspot". USGS. http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/Hawaiian.html. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 "Geological Map of the State of Hawaii". USGS Hawaii geology pamphlet. USGS. 2007. http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2007/1089/Hawaii_expl_pamphlet.pdf. Retrieved 2009-04-12. pp. 44–48

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Complete Report for Mauna Kea Volcano (Class B) No. 2601". USGS. 26 October 2009. http://gldims.cr.usgs.gov/webapps/cfusion/sites/qfault/qf_web_disp.cfm?disp_cd=C&qfault_or=5107&ims_cf_cd=cf. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hawaiian Volcano Obserrvatory: Photo Information". Photo description. USGS. 13 March 1998. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanoes/maunakea/keasnow_caption.html. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Hawaiʻi: Hawaii's Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy". Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources. 1 October 2005. http://www.state.hi.us/dlnr/dofaw/cwcs/files/NAAT%20final%20CWCS/Chapters/CHAPTER%206%20hawaii%20NAAT%20final%20!.pdf. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 "Mauna Kea Comprehensive Management Plan: UH Management Areas". Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. January 2009. http://www.maunakeacmp.com/files/MaunaKea_CMP.pdf. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ "What in the world is the Hilo Ridge?". Hawaii Volcano Observatory - USGS. 8 January 1998. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/1998/98_01_08.html. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Impermeable beds trap rain and snow at Mauna Kea's Lake Waiau". Hawaii Volcano Observatory - USGS. 19 June 2003. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/2003/03_06_19.html. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ Watson, John (18 July 1997). "Lava Flow Hazard Maps: Kohala and Mauna Kea". USGS. http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/hazards/maunakea-kohala.html. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ "Final Environmental Statement for the Outrigger Telescopes Project: Volume II". NASA. February 2005. p. 67. http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov/Outrigger/finalDocuments/fullDocument/OTP-FEIS-Volume-II.pdf. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 "Culture: The First Arrivals: Native Hawaiian Uses". Mauna Kea Mountain Reserve Master Plan. University of Hawaii. http://www.hawaii.edu/maunakea/5_culture.pdf. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Mountain Deities". Na Maka o ka Aina. http://www.mauna-a-wakea.info/maunakea/F1_mtndeities.html. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Looking towards Mauna Kea volcano from the Mauna Loa Solar Observatory". USGS. 9 August 2005. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/archive/spotlight_images/mlso_mkeaBack.html. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Mauna Kea". SOEST. 25 February 2008. http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/GG/HCV/maunakea.html. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ "Visitor Information Station - Bulletin". Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/info/vis/bulletins.html. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ "Mauna Kea - from mountain to sea: Lake Waiau". Na Maka o ka Aina. http://www.mauna-a-wakea.info/maunakea/A2_lakewaiau.html. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Mauna Kea". Summitpost.org. 2006. http://www.summitpost.org/mountain/rock/150854/mauna-kea.html. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 23.9 Juvik, J. O; J. O. Juvik and S. P. Juvik (August 1984). "Mauna Kea and the Myth of Multiple Use: Endangered Species and Mountain Management in Hawaii". Mountain Research and Development (International Mountain Society) 4 (3): 191–202. doi:10.2307/3673140. http://www.jstor.org/pss/3673140. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ "Kaluakauka Revisited: the Death of David Douglas in Hawaii". Hawaiian Journal of History (Hawaiian Historical Society, Honolulu) 22: pp. 147–169. 1988. http://hdl.handle.net/10524/246.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 "Recreation: Enjoying Mauna Kea's Unique Natural Resources". Mauna Kea Mountain Reserve Master Plan. Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. http://www.hawaii.edu/maunakea/7_recreation.pdf. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Duffy, Dr. David Cameron (1990). "Changes in Vegetation Since 1850". http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/faculty/duffy/book/1990_chap/10.pdf. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ Duffy, Dr. David Cameron. "Alien Plants". http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/faculty/duffy/book/1990_chap/13.pdf. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Mauna Kea Ice Age". Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources. http://hawaii.gov/dlnr/dofaw/nars/reserves/big-island/maunakeaiceage. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ "A Remarkable New Micropterous Nysius Species from the Aelion Zone of Muana Kea, Hawaiʻi island". International Journal of Entomology (Bernice P. Bishop Museum) 25 (1): 47–55. 26 April 1983. http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/pi/pdf/25%281%29-47.pdf. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Wekiu bugs-life on top of a volcano". Volcano Watch. Hawaii Volcano Observatory - Hawaiian Volcano Observatory - USGS. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/volcanowatch/1999/99_05_20.html. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Scrowcroft, Paul G. (1983). "Tree Cover Changes in Miimane (Sophora chrysophylla) Forests Grazed by Sheep and Cattle". Pacific Science (University of Hawaii Press) 37 (2). Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ "Palila v. Hawaii Dept. of Land & Natural Resources, 639 F. 2d 495 - Court of Appeals, 9th Circuit 1981". Google Scholar. Google Inc.. http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8158542596159694344&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Mauna Kea State Recreation Area". Hawaii State Parks. Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources. http://www.hawaiistateparks.org/parks/hawaii/maunakea.cfm. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ Takaki, Ronald (April 1994). Raising Cane: The World of Plantation Hawaii. New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0791021781.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 "Welcome to Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge". US Fish and Wildlife Service. 6 April 2010. http://www.fws.gov/hakalauforest/. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 "About Mauna Kea Observatories". Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/mko/about_maunakea.shtml. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Mauna Kea Science Reserve Astronomy Development Plan 2000-2020 -- Summary". Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. August 1999. http://www.hawaii.edu/maunakea/appendix_a.pdf. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ "1: Observing the Universe" (Hardcover). DK Space Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley. 1999. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-7894-4708-8. "[The] Keck mirror alone has a total light-collecting area 17 times greater than the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble can see more clearly, but the Keck Telescopes can see farther."

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Mauna Kea Telescopes". Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/mko/telescope_table.shtml. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hubble". NASA. http://pds.jpl.nasa.gov/planets/welcome/hubble.htm. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Thirty Meter Telescope Selects Mauna Kea". Press release. Caltech, University of California, and the Association of Canadian Universities for Research in Astronomy. 21 August 2009. http://www.tmt.org/news-center/thirty-meter-telescope-selects-mauna-kea. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "University of Hawaii Develop New telescope for "Killer" Astroid Search". Press release. Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. 8 October 2002. http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/~kaiser/pan-starrs/pressrelease/.

- ↑ Dayton, Kevin (23 May 2003). "Tiny bug may affect astronomy plans". The Honolulu Advertiser. http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2003/May/23/ln/ln11a.html. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hawaii Island". Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources. http://www.hawaiistateparks.org/parks/hawaii/. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Mauna Kea Hazards: Please Read Before Travelling Above Hale Pohaku". Safety Leaflet. Institute for Astronomy - University of Hawaii. http://irtfweb.ifa.hawaii.edu/observing/safety/MK_Hazards.pdf. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

Further reading

- Macdonald; Gordan A. Macdonald, Agatin T. Abbott, and Frank L. Peterson. (1983). Volcanoes in the Sea: The Geology of Hawaii (2nd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824808327. http://books.google.com/?id=IuADTBNksO0C&lpg=PP1&dq=Volcanoes%20in%20the%20Sea%3A%20The%20Geology%20of%20Hawaii&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q.

- Wolfe, E.W.; W.S. Wise, and G.B. Dalrymple (1997). The geology and petrology of Mauna Kea volcano, Hawaii : a study of postshield volcanism. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. USGS.

- Herzberg, Claude (30 November 2006). "Petrology and thermal structure of the Hawaiian plume from Mauna Kea volcano". Nature (Nature Publishing Group) 444: 605–609. doi:10.1038/nature05254. PMID 17136091. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v444/n7119/abs/nature05254.html.

- Robinson, Joel E.; Joel E. Robinson and Barry W. Eakins (1 March 2006). "Calculated volumes of individual shield volcanoes at the young end of the Hawaiian Ridge". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. Growth and Collapse of Hawaiian Volcanoes 151 (1-3): 309–317. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.07.033. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0377027305003252.

- Porter, Stephen C. (June 1973). "Stratigraphy and Chronology of Late Quaternary Tephra along the South Rift Zone of Mauna Kea Volcano, Hawaii". Geological Society of America Bulletin (Geological Society of America) 84 (6): 1923–1940. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1973)84<1923:SACOLQ>2.0.CO;2. http://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/84/6/1923.

- Woodcock, A. H.; Furumoto A. S., Woollard G. P. (1970). "Fossil ice in hawaii?". Nature (Nature Publishing Group) 226 (5248): 873. doi:10.1038/226873a0. PMID 16057558. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v226/n5248/abs/226873a0.html.

- Jenny M. Rikera, Katharine V. Cashmana, James P. Kauahikauab and Charlene M. Montierth (10 June 2009). "The length of channelized lava flows: Insight from the 1859 eruption of Mauna Loa Volcano, Hawaiʻi". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research (Elsevier B.V.) 18 (3-4): 139–156. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.03.002. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0377027309001395.

- Sakai, Ann K.; Wagner, Warren L.; Mehrhoff, Loyal A. (2002). "Patterns of Endangerment in the Hawaiian Flora". Systematic Biology (Oxford University Press) 51 (2): 276–302. doi:10.1080/10635150252899770. http://sysbio.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/51/2/276.

- Lawrence R. Walker and Elizabeth Ann Powell (July 1999). "Regeneration of the Mauna Kea silversword Argyroxiphium sandwicense (Asteraceae) in Hawaii". Biological Conservation (Elsevier B. V.) 88 (1): 61–70. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00132-3. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006320798001323.

- Onopa J., Haley A., Yeow M. E. (2007). "Survey of acute mountain sickness on Mauna Kea". High Altitude Medicine & Biology (Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.) 8 (3): 200–205. PMID 17824820. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17824820?dopt=Abstract.

External links

- Geology

- Mauna Kea Summary. Global Volcanism Program.

- Mauna Kea. Hawaii Center for Volcanology.

- Astronomy and culture

- Mauna Kea Observatories. Tour of Mauna Kea's summit facilities.

- Mauna Kea Visitor Information. Information pertaining to visiting the summit telescopes.

- "Mauna-a-Wakea", cultural information site for Mauna Kea.

- Ecology and management

- Office of Mauna Kea Management. Plan for land management.

- Mauna Kea Ice Age Reserve. Department of Land and Natural Resources.

- Mauna Kea Comprehensive Management Plan. "About."

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||